Joshua Oppenheimer: why I returned to Indonesia’s killing fields

In 2012, director Joshua Oppenheimer exposed how those behind the Indonesian genocide still revel in their crimes 50 years on. His new film, The Look of Silence, follows one grieving family trying to understand why

|

Joshua Oppenheimer is showing me a copy of a handmade book entitled Dew of Blood. Written and illustrated by a former village school teacher called Amir Hasan, it describes a series of killings he helped carry out as a death squad leader during the Indonesian genocide of 1965. That was the year in which more than a million suspected communists were executed following a military takeover.

The passage Oppenheimer haltingly translates describes the murders of Hasan’s first five victims, whose bodies were thrown into a well on a palm oil plantation. It is written as a kind of dark fantasy complete with graphic drawings and collages. “He imagines that the ghosts of the victims rise up out of the well to describe the ensuing killings,” says Oppenheimer, “so he has drawn these gory pictures and used generic comic-book imagery to record what he sees as his heroic role in the mass killings of his fellow Indonesians.”

As documentations of a genocide go, it is perhaps unique, being the testimony of a perpetrator rather than a survivor and one recounted with apparent glee and lack of remorse as a kind of violent, self-glorifying graphic novel.

Dew of Blood is an important document for Oppenheimer, who won awards for his 2012 documentary The Act of Killing, and for Adi Rukun, the young Indonesian man at the centre of his new film, The Look of Silence. The book ends with a list of names of the dead alongside the date, time and location of each killing. Among them is Adi’s older brother, Ramli. A footnote describes how he was taken from a political prison on the night of 27 January and died in a plantation close to his family home in the early hours of the morning. Ramli had been captured by the army as a suspected subversive and stabbed in the stomach. He escaped and fled to his parents’ home in a village in North Sumatra, where Amir Hasan and his accomplice, Inong, recaptured him, telling his mother they would take him to hospital in nearby Medan. Instead, he was put in a truck with other prisoners and driven to a secluded spot a few miles from his home, where he was dragged, almost naked and with his hands tied, along a path to the river, all the while crying and pleading for mercy. There, Hasan and Inong mutilated him further with machetes, cutting off his penis and dumping his body into the river. Among survivors’ and victims’ families, Ramli’s name has since become, as Oppenheimer puts it, “a synonym for the killings in general”.

Ramli’s ghost haunts The Look of Silence, a film that Oppenheimer sees as “completing” his 2012 documentary, The Act of Killing. In that film, heoverturned documentary conventions by choosing not to investigate in depth the terrible events of 1965 and 1966, but instead explored the horror and its lingering presence in collaboration with the killers, many of whom were leaders of an Indonesian paramilitary force called Pancasila Youth. He convinced former death squad members, including his primary subject, Anwar Congo, to re-enact some of their more gruesome killings in the swaggering style of the hardcore gangster films they revere. This they did with apparent relish, boasting about their exploits, acting out their gruesome deeds – victims despatched by machete or garrotting by wire – in elaborate detail and staging surreal fantasy interludes to symbolise their triumph over the evils of communism. The film was almost universally critically lauded on its release and went on to win more than 70 international awards including a European Film Award (2013) and a Bafta (2014).

Aside from a protracted scene in which Amir and Inong act out the torture and killing of Ramli in a similarly grotesque and gleeful manner, The Look of Silenceis, generally speaking, a more restrained, quietly haunting film, a meditation on the lingering and pervasive psychological fallout of the genocide. The horror, though it underlies every frame of the film, is subsumed into the intimate story of a grieving, traumatised family: two elderly parents, Rohani and Rukun, and their youngest son, who, 50 years after the genocide, are still living in a village where the murderers of their son and countless other victims are either feared or treated as heroes.

“My task in The Act of Killing was to expose the escapism and fantasies of the perpetrators,” says Oppenheimer, “as well as the lies they tell so they can live with themselves, but also how they continue to impose these fantasies and lies on those around them and on the relatives of the dead. My task in this film is to show what the frightened silence of the survivors, and indeed of the society, looks like. It divides neighbours from neighbours and even relatives from relatives in an abyss of trauma. It is a fear that will never go away until it is addressed. By looking at a single family, I am going microscopic to show the much broader picture. That intimacy makes us perceive them as human beings, not victims. Adi could be my brother.”

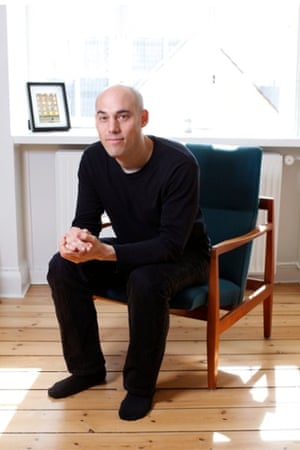

I have travelled to Copenhagen to meet Oppenheimer in the spacious, spartan apartment close to the riverfront that he has recently bought with his Japanese partner, Shu. Having been asked to remove my shoes at the front door, I enter a minimalist open-plan space, where every item of carefully chosen Scandinavian furniture whispers consummate good taste. Over green tea, Oppenheimer chooses his words with equal care and, though soft-spoken, exudes the intensity of the truly committed. Andrea Luka Zimmerman, a German artist and film-maker based in London, who has known Oppenheimer since the late 1990s, when he was studying for a PhD at Central St Martin’s, describes him as “one of the most rigorous people I know, and deeply caring, both to his friends and to those with whom he makes work. He never rests until he has given his best and this goes for everything he does from cooking to film-making.”

Born in Texas in 1974, he grew up in Washington DC and Santa Fe, New Mexico. His political consciousness was shaped to a great degree by his upbringing: his father was a political science professor and his mother by turns, a trade union activist, a labour lawyer and an environmental lawyer. His father’s parents fled Germany just in time to escape the Holocaust. “I heard about the Holocaust before hearing the Cinderella story or watching Peter Pan,” he says. “I grew up with the message that we should try to understand that the aim of all politics, art and morality was to try to prevent these things ever happening again to anyone.”

Oppenheimer describes himself as “culturally Jewish – secular rather than religious”. He is alarmed by the rise of extreme rightwing politics and xenophobia across Europe. “Even here in Denmark, a liberal society, you have the Social Democrat party putting up signs saying we are going to get tough on asylum seekers,” he says. “It feels like there is definitely something in the air.” Has he felt it personally? “No. But, then I’m a ‘good’ immigrant. I have a British and an American passport. I’m acceptable and totally accepted.”

Oppenheimer first met Adi Rukun in 2003, having heard the story of Ramli’s death from several survivors of the killings. Adi is the still centre of The Look of Silence, a quiet, determined, emotionally burdened man who works as an optician. Having initially helped and become friends with Oppenheimer during the making of the first film, Adi chose to confront the past head on and at considerable personal risk. It is his calm, quizzical face that Oppenheimer returns to throughout the film, often shooting it in close-up as Adi watches, with intense concentration, video footage of Hasan and his accomplice replaying their gruesome killing of his brother. And it is Adi that Oppenheimer’s camera tracks as he sets out to confront the leaders of the death squads who murdered Ramli, having gained access to their homes by arranging to test their eyes.

First he meets Inong who, wearing the heavy optical frames Adi has placed over his eyes, speaks freely about his crimes, how he once cut off the breast of a communist woman who had been given up for execution by her own brother and how, like many of the killers, he drank the blood of his victims in the belief that it would stop him going mad amid the relentless slaughter. As with The Act of Killing, this is a journey into the abyss that grows darker with every step.

“You have to understand that Adi is an exceptional individual in his empathy, his patience and his desire to understand,” says Oppenheimer. “He is not seeking revenge on those he confronts, rather an acknowledgment from them of the terrible cost of their crimes and how the fear they instilled still lingers. What he is asking is: how can these people have done this and now live around us and keep that fear alive?”

Since the film’s completion, Adi and his family have been relocated for their safety to another part of Indonesia where, says Oppenheimer, “there is a strong community of activists and critical journalists and he is regarded as a hero”. When I interview Adi by email, he is about to open an optometrist shop and his mother, over 100 years old and a mischievous, defiant presence in the film, is he says “more lively than she’s been in 10 years”.

His father, Rukun, wizened with age, blind and almost totally deaf, is another haunting presence in the film. He died in 2013. One of the film’s more disturbing scenes shows Rukun trapped in his own yard, confused and agitated about where he is. It is an upsetting, protracted moment in the narrative, so much so that I admitted to Oppenheimer that I wasn’t sure why it had been included.

It turns out that it was actually filmed by Adi in 2010 and was the pivotal moment in his decision to confront the perpetrators. “That was a terrible and sad day for me and my mother,” recalls Adi. “It was the first day my father could no longer remember me, my brothers and sisters or my mother. I realised it was too late for him. He would die with the trauma from Ramli’s murder, and he would never heal, because he had forgotten the son whose murder destroyed our family. All he remembered was the fear, like a distant echo from a sound long forgotten. I realised I did not want my children to live their lives with this fear, and I felt the only way of preventing this was for me to meet the perpetrators of my brother’s murder.”

What was going through Adi’s mind as he walked up the path to Inong’s compound? “Meeting Inong, I was not afraid for our security,” he replies, “We chose him as the first one to confront because he was not connected to the powerful perpetrators who could endanger us. If I look nervous when I am entering his house, it is because I was worried that Inong would not be able to admit he was wrong.”

Could Inong have said anything that might have assuaged Adi’s family’s grief? “I guess I was naive, but I thought that, when they saw I was not coming for revenge, they would be relieved and finally be able to apologise. Then I could accept them again as human beings and we could live together as neighbours, without fear.”

In the event, Adi is met with suspicion, anger and denial. In one instance, when he confronts Amir Siahaan, the commander of a local branch of another paramilitary group who signed the death reports of about 600 people, he is given a not-so-veiled threat about the risks of being a “subversive”. Unfazed, Adi asks: “If I came to you like this during the dictatorship, what would have happened?” The commander pauses, staring straight at him, and says quietly: “You can’t imagine what would have happened.”

Towards the end of the film, Adi also confronts the family of Amir Hasan, who died not long after being filmed re-enacting Ramli’s killing. Hasan’s wife and sons react with a mixture of denial and outrage and the scene ends abruptly when one son calls the police.

“I had a sense of foreboding that the whole effort to get the perpetrators to apologise would fail,” admits Adi, when I ask him if he was surprised by the response. “Joshua had already told me he thought this would happen and the conflict at the end confirmed my fears that we would not get any expression of remorse. But still I think the reason they were unable to apologise to me is not because they were afraid of me, or even of justice. They are afraid of themselves – their own guilt, their own conscience.”

I ask Adi about the impact of Oppenheimer’s two films in Indonesia. “They have opened many people’s eyes,” he says. “The media in Indonesia now talk about the past in a very different way. But we need more Indonesians to see both films. I do not know the impact of The Look of Silence in my village, because my mother and I left the village before the film was released, but from what I hear people there now know that the world and the country finally see that what happened 50 years ago was wrong. It is now up to today’s government to start a genuine reconciliation and rehabilitation process. Fifty years is already too long.”

Oppenheimer is uncomfortable with being described as an activist, but his politics are fuelled by anger at the stark injustices of global capitalism and our collusion as consumers. “The fear I felt in Indonesia is present elsewhere and is, in fact, an essential ingredient of our global economy,“ he says, “We know, for instance, that the people who made our smartphones may have been suicidal, in despair because of the conditions of the factories they worked in, but we don’t want to think about it or even look at it. I believe that by looking or speaking out, we are compelled to maybe act. Otherwise we retreat into fantasies that divide us from each other and from ourselves and allow people to retreat into the kind of fantasies in which they can describe the migrants who are coming to Britain as cockroaches.

“In the rich world, we have a slightly wider compass of freedom and debate, but that is closing. On the mainstream airwaves in America, you can hear people defend torture. Our previous vice-president [Dick Cheney] views waterboarders as national heroes. These are some of the reasons why I don’t want people just to see these films as a window on to the other side, but as a mirror.”

It was his fascination with our ability to lie to ourselves that first brought Oppenheimer to Indonesia in 2001. There, with creative collaborator Cynthia Cynn, he set about enabling a group of oil palm plantation workers to make a documentary. The Globalisation Tapes, released in 2003, exposed the harsh treatment of the workforce by a Belgian-owned company, which included female workers being forced to spray deadly herbicides without protective clothing and the use of hired paramilitary members to threaten those who tried to protest or form a union.

“When the company brought in local gangsters from the Pancasila Youth, the workers dropped their demands immediately,” says Oppenheimer. “That was the shadow of 1965. Most of the workers’ parents or grandparents were killed then, not because they were communists, as the state claimed, but because they were in a large and organised union. That’s when I decided I’d spend as many years of my life as it took to bring this to attention.”

Oppenheimer first became interested in film-making as an undergraduate at Harvard, where he studied theoretical physics and cosmology - “I was preoccupied, as I still am, with what we are, where we come from and what we are made of” - before switching to philosophy. Midway through his scholarship, he switched again, this time to film-making, cramming a four-year study programme into two years. “I didn’t really get any rigorous background in film history,” he admits.He cites the great Serbian experimental director Dušan Makavejev, who taught him at Harvard, and Ozu, Robert Bresson and Werner Herzog as his prime influences rather than traditional documentary film-makers. (Werner Herzog and American documentary maverick, Errol Morris, are credited as executive producers on The Act of Killing and both have endorsed his work enthusiastically.) “At Harvard, direct cinema was the core of the film department,” he says, “and most of the students were trying to make socially conscious works, but I was trying to combine fiction and non-fiction to show how our seemingly factual world is constituted through fantasy and stories.”

There’s an intriguing scene in The Look of Silence in which Adi tells his wife, much to her dismay, that he has approached one of his brother’s killers. Filmed in both long shot and close-up as they sit side by side on concrete steps outside their house, it is a prolonged study of things said and unsaid. Above all, it is Adi’s resigned silence in the face of his wife’s concern that gives the scene such an intimate power. But there is a camera present. I put it to Oppenheimer that, to some degree, the intimacy is therefore an illusion and the conversation, though sincere, must surely be shaped by the couple’s awareness of being filmed.

“In that instance, the camera is heightening the occasion that we have set up together. I don’t believe that if you film anyone for long enough they forget the presence of the camera,” says Oppenheimer. “They might become used to it but it always affects their behaviour. The camera is never a window on to a pre-existing reality. Just imagine any intimate, problematic conversation with someone you love and then imagine it with a camera there. You could never confuse those two situations, not least because people behind the camera have the power to shape your public image for the rest of your life.”

One cannot help but wonder, then, why the likes of Anwar Congo and Amir Hasan ever agreed to collaborate with Oppenheimer, let alone in such a recklessly self-exposing way. But collaborate they did, bolstered, he says, by their continuing immunity and convinced that their grotesque re-enactments would make them even more heroic to many in the country. Oppenheimer uses the term “cognitive dissonance” more than once to describe what he sees as their complex psychological state. “Their boasting is helping maintain a regime of fear, but it is not a manifestation of genuine pride. You don’t brag about something you are proud of; you brag to compensate for insecurity. These guys are not proud. In fact, the opposite is true. It’s a desperate attempt to live with what they have done. It’s the very opposite of what it appears to be.”

More than once, Oppenheimer emphasises his belief, implicit in his films, that the killers are not monsters, but ordinary people caught up in a political ideology in which the killing of suspected communists was not just supported, but expected. “I don’t like the escapist notion that we are not like them,” he says. “That there are monsters over there, but not over here. That’s too simplistic.”

Nevertheless, I counter, there is a series of ethical choices that lead to a person becoming a mass killer. The perpetrators had a choice: they weren’t forced into it. “Of course, there are choices,” he says. “None of them killed because they were going to be killed. They chose to kill in a moment of exorbitant selfishness, a suspension of their regard for others, a suspension of their empathy. But it is only a suspension I believe. Some of them could be sociopaths, but as Primo Levi said of the Holocaust, there may be monsters out there, but they are too few to worry about. I refuse to comfort myself with the moral lie that these men have done something monstrous, and consequently are monsters, and therefore I am not like them.”

Has he kept in touch with Anwar? “I’ve talked to him maybe six time since The Look of Silence came out.” Has Anwar’s life altered since the film was released? “Yes, I think he is less involved with the paramilitary group.” Have they disowned him or is he distancing himself? “A little bit of both maybe. They haven’t threatened him or blamed him or scapegoated him, which is one of the reasons I kept in touch frequently when we were releasing the film. I was vigilant to see that would not happen because it would be wrong for him to be attacked by the other perps for making the film. But my understanding is that he is as OK as a man like him can hope to be. He’s older and he’s not suffering from nightmares as much.”

So, you feel empathy for Anwar? “Of course. The whole premise of the film is that, through my closeness to him, viewers are forced to become intimate with him also and most viewers, I think, will feel some empathy with him, though not sympathy, which is a very different thing. And, of course, some viewers will resist that, kicking and screaming, and say, ‘These men are monsters! I shouldn’t be feeling this way.’ I think that was Nick Fraser’s reaction.”

Against the tide of praise for The Act of Killing, Nick Fraser, commissioning editor of the BBC’s Storyville documentary series, was one of the few dissenting voices. In this newspaper, under the headline “Don’t give an Oscar to this snuff movie”, Fraser expressed his distaste for Oppenheimer’s approach. “I find the scenes where the killers are encouraged to retell their exploits, often with lip-smacking expressions of satisfaction, upsetting not because they reveal so much, as many allege, but because they tell us so little of importance … I’d feel the same if the film-makers had gone to rural Argentina in the 1950s, rounding up a bunch of ageing Nazis and getting them to make a film entitled ‘We Love Killing Jews’.”

As I reprise Fraser’s criticisms now, Oppenheimer tenses. “It was actually some friends in Indonesia who drew my attention to Fraser’s piece and to the comments posted underneath, which were mostly from Indonesians. As one of them pointed out, the only people who would agree with Fraser in Indonesia are the military. Personally, I couldn’t understand why he took time to write such a lengthy piece without acknowledging the film’s impact in Indonesia. This is a film about impunity and exposing the lies that underpin it, not a film in which we are trying to make visible a forgotten genocide. I suspect Fraser, as a documentary commissioner, is uncomfortable with abandoning the most pervasive escapism of all that we have in liberal democracies – that we have nothing to do with this violence, that these men have nothing to do with us, that they are the other.”

If Oppenheimer’s methods are provocative, so is his political message: that we in the west are an essential part of the horror, injustice and silence. Both the American and UK governments, he reminds us, sanctioned the mass killings of so-called communists in Indonesia in 1965 at the height of the cold war – “the UK was the biggest supplier of weapons”. When he drew attention to Britain’s role at the Baftas last year, the BBC, much to his dismay, removed the reference when it broadcast his speech.In The Look of Silence, he uncovers a long-lost late-60s NBC TV news broadcast from Indonesia in which the reporter praises the country’s beauty and celebrates the recent genocide as “the single biggest defeat handed to communists anywhere in the world”. It then cuts to footage of survivors held in a prison camp and forced to work “but this time as prisoners and at gunpoint”. The company they are working for as slave labour is Goodyear.

“This was reported on US television in 1967,” says Oppenheimer. “Because of the lens of ideology, Americans did not perceive this as a replay of what happened commercially and industrially at Auschwitz. This is a profound stain on America’s claim to be a force for justice and democracy in the postwar world.”

Was there a personal cost to making these films, in confronting this kind of horror? He pauses for a long moment. “Well, I wasn’t physically afraid during the making of The Act of Killing, but I was emotionally afraid. The scene where Anwar butchers the teddy bear in the director’s cut of the film triggered eight months of nightmares and insomnia. It was one of the deepest, most important things I have ever seen. And, since the film was shown in Indonesia, I have been receiving regular death threats from the paramilitary leader’s henchmen.”

Oppenheimer is tightlipped about his next project but tells me it will not be about Indonesia, not least because it would now be difficult for him to return there. “I don’t see what I do as storytelling, it’s more of a deep exploration. I can’t do that from a place of exile.” Given all that he has uncovered, is he optimistic that film-making can make a change? He smiles ruefully. “Neither of my films paints a rosy picture of the human condition and, I suppose, you could not make films that are so damning if you were a positive-thinking optimist. And yet, conversely, you would not spend a decade of your life doing that if you were hopeless.”

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jun/07/joshua-oppenheimer-the-look-of-silence-interview-indonesia?CMP=fb_gu